I wonder how many people realise that Australia’s concept of a minimum wage began with the landmark Harvester Judgment of 1907, a case that forever changed industrial relations in the country?

Fewer still might know that the man at the heart of that case was also behind one of the most significant agricultural inventions to come out of Australia; the combine harvester. Alongside the stump jump plough, the combine harvester was one of two inventions I learned about from a young age as being quintessentially Australian. Yet the origins of this groundbreaking machine, now used by the thousands worldwide, are largely forgotten.

Here is the story of the machine that revolutionised farming around the world, and the forgotten legal legacy it left in its wake.

The Harvester Decision of 1907 is often hailed as a landmark moment; not just in Australia, but globally; for establishing the principle that a fair wage should be based on the needs of a worker and their family, not simply on market forces.

Behind this revolutionary ruling was a man whose mechanical invention transformed agriculture, and whose name, Hugh Victor McKay, became as closely associated with industrial reform as with innovation in the paddocks.

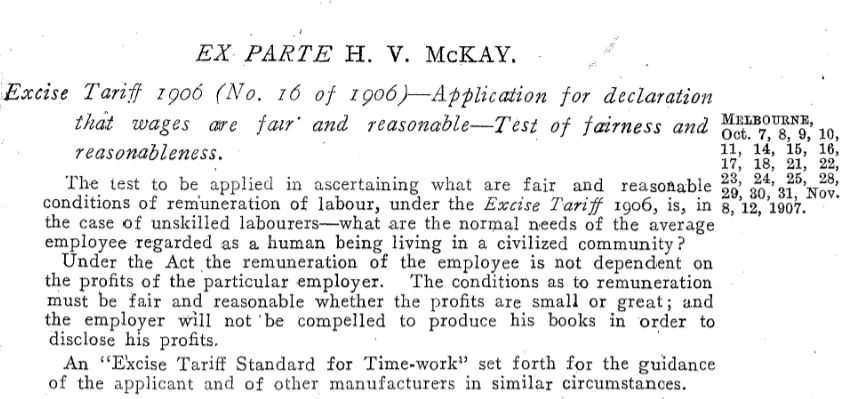

The case was presided over by Justice H.B. Higgins, who was asked to determine whether McKay, owner of the Sunshine Harvester Works, was paying “fair and reasonable” wages, a requirement for exemption from excise duty. Rather than defer to prevailing market rates, Higgins declared that a worker should earn enough “to live in frugal comfort” with his wife and three children.

It was a radical shift, embedding a social and moral standard into economic policy.

Hugh Victor McKay (1865–1926) was born at Raywood in Victoria, the fifth of 12 children of Nathaniel McKay and his wife Mary. They had emigrated to Australia from County Monaghan in Ireland in 1852, drawn like thousands of others to the Victorian goldfields.

Nathaniel abandoned gold mining to become a stonemason and later a farmer. The children had limited schooling, but all eight sons became successful in a variety of fields. Hugh Victor left school when he was 13 to help on the family farm, and it was in agriculture that he was to make a great impact.

As an adult, he became aware of a Victorian government prize offered to anyone who could build a machine capable of combining the four activities required in harvesting cereal crops: stripping, threshing, winnowing, and bagging.

In 1885, with his father and brother John, he assembled a stripper-harvester from pieces of equipment on the farm. This was a prototype and Hugh Victor went on to build harvesters under contract as the McKay Harvesting Machinery Company. The company traded successfully until the Australian banking crash of 1892-93 caused its closure.

McKay was not deterred and with the backing of rural businessmen he established The Harvester Company and produced an improved machine he called “the Sunshine”. Orders trickled in at first, but as more farmers bought Sunshine harvesters, production increased. Fifty were sold in 1896 and sales rose to 500 in 1901. An export trade developed with machines being sent to South Africa and Argentina.

'Sunshine' stripper-harvester made by H.V. McKay Pty Ltd

By 1905 the Sunshine Harvester works in Ballarat was employing 500 people. A succession of improvements to the manufacturing process improved efficiency and output continued to grow - some 1,916 machines were sold in 1905-6. McKay seized the opportunity to purchase The Braybrook Implement Company on the outskirts of Melbourne in order to expand Sunshine Harvesters.

RELIC FROM THE PAST: Allen Webb, Neil Hateley, Colin Webb, Euan Hateley and Andrew Hateley admire the historic H.V. McKay harvester before moving it to Natimuk. The machine is more than a century old. Picture: KATE HEALY

But as the machines rolled off the production line in increasing numbers, tensions in the factory floor would soon trigger a turning point in Australian labour history.

Mckay sought tariff protection from foreign competitors that he asserted were copying Sunshine harvesters.

Ever the strategist, McKay sought tariff protection from foreign competitors, claiming that manufacturers overseas were imitating his Sunshine harvesters and undercutting local prices. He argued that without government intervention, Australian ingenuity and enterprise would be swamped by cheaper, copycat imports. This appeal to economic nationalism placed McKay at the centre of a larger debate about protecting Australian industry, and ultimately drew him into the legal and political battles that would culminate in the Harvester Judgment.

The Harvester Judgement was the first decision handed down by Mr Justice Higgins, the new President of the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court created in 1904. In his judgement Higgins defined a “worker” as : ‘a… human being in a civilized community entitled to marry and raise a family.’

He went on to say that “The wages paid had to reflect the reality of a worker providing the basic needs for a family of five and to define this Higgins took the radical approach of interviewing not only male workers but also their wives.”

In his judgement, Higgins calculated that a fair and reasonable wage for manual workers was seven shillings per day or 42 shillings per week. Higgins’ ruling essentially laid the foundation for the living wage movement around the world.

McKay did not accept the judgement and appealed to the High Court which, in 1908, overturned it as unconstitutional, invalid and void. It ruled that the Constitution permitted the Commonwealth to levy Customs and Excise Duties but not to determine wages and working conditions. Higgins was also a judge on the High Court bench.

In 1910 the Agricultural Implement Makers’ Union called a strike to which the company replied with a lock-out that lasted 13 weeks and left the union bankrupt. The impacts on industrial relations in Australia lasted for decades and the concept of a minimum wage was to endure.

Though the High Court overturned Higgins’ ruling, the moral and social principle it introduced - that a wage should support a decent life - echoes today in Australia’s minimum wage system, reviewed annually by the Fair Work Commission.

In the wake of these disputes, McKay turned his attention to fostering industrial harmony.

McKay decided to invest in industrial peace by creating a company town at Braybrook, which was, and still is, now known as Sunshine. Modelled on examples such as Port Sunlight (Lever Brothers) and Bourneville (Cadbury’s) it provided housing and sporting and cultural facilities. Several McKay families lived at Sunshine including Hugh Victor’s until he moved to a grand mansion, “Rupertswood”, near Sunbury.

The Sunshine Harvester Works was the largest manufacturing company in Australia by the 1920s with buildings extending over 12 hectares. By this stage it was making a wide range of agricultural machines and continued to innovate and invest. Henry Victor ruled the organisation as a director with absolute control which continued until his death from lung cancer at the age of 60 on May 21st 1926. The business continued, eventually merging with that of Massey Harris.

Hugh Victor McKay paid at least one visit to Ireland. In the collection cared for by Museums Victoria is a photograph of him with a group enjoying a ride in a horse-drawn carriage somewhere in Ireland and another shows him and Mrs McKay at the Giants Causeway, County Antrim. Several photos feature HV MacKay and friends in Ireland riding in a white Lanchester touring car. It is likely that the Irish visit took place after a visit to the Western Front in 1914. Another image in the Museums Victoria collection is of him looking at the shattered remains of the medieval Wool Hall in the Belgian town of Ypres.

Hugh Victor McKay and his companions sitting in a horse-drawn carriage in Ireland circa 1912. Photograph: Museum Victoria

The HV McKay Charitable Trust, created at the time of his death, carries his name on. It offers support to community ventures in rural Australia. One of his last acts was to lay the foundation stone of the Presbyterian Church at Sunshine a few days before his death. It is situated in the HV McKay Memorial Gardens that continue to provide a pleasant amenity for the people of Sunshine.

In 1953 The Sunshine Harvester Co merged with the Canadian implement manufacturer Massey- Harris for which it had been the exclusive Australian distributor since 1930. The name changed to H. V. McKay Massey Harris Limited then in 1958 Massey Harris merged with the British tractor manufacturer Ferguson. In 1958 the name was changed again to Massey Ferguson Limited.

The Ferguson tractor is embedded in Australia’s agricultural history as one of the enduring mainstays of countless farms across the country. There are plenty of little Grey Fergies and Red Fergies still in use today.

When our family had the farm at Kerang I had four Red Fergies. They would be nearly 70 years old now and one that I kept was in regular use at my brother’s vineyard until three years ago when I gave it to my niece who bought a small property at Swan Hill. It is still going strong and never misses a beat.

Unfortunately the march of overseas manufacturing caught up with Massey Ferguson like it did with many other iconic Aussie manufacturers. Production at Sunshine ceased in 1986 and the whole complex was demolished in 1992 save and except some key features which are listed on the Victorian Heritage Register and still stand today.

In 1985, the City of Sunshine issued a medal (NU 20682) to commemorate Victoria's sesquicentenary and shortly afterwards the Sunshine Harvester Works closed its gates for the last time, with the former factory site being cleared to make way for a carpark, community centre and shopping mall.

In producing the foregoing, I am indebted to Dr Patrick Greene, CEO and Director of EPIC – The Irish Emigration Museum in Dublin. The EPIC Museum tells the stories of Irishmen who emigrated, found success in foreign lands, and helped shape the world.

Footnote from Monty:

There’s no clear evidence that the accusations McKay made about foreign competitors copying the Sunshine harvester ever led to formal legal action or international patent disputes. While McKay did secure multiple patents for his designs (both in Australia and abroad), and was known to be protective of his intellectual property, there’s no record of successful prosecution or trade retaliation against specific foreign manufacturers for “copying” his machines.

However, what did follow was a political and economic campaign - McKay lobbied heavily for tariff protection, using the threat of foreign imitations as part of his case to the Commonwealth government. His argument was less about prosecuting individual infringers and more about convincing lawmakers that Australian industry needed shielding from cheaper imports......

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS