The Battle of Long Tan took place on August 18, 1966, in the Phuoc Tuy Province of South Vietnam. It was part of Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War as part of its commitment to the United States' efforts to counter the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. The region's dense jungles, muddy terrain, and unpredictable weather added to the complexity of the conflict. The Australian soldiers were part of the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, and were led by Major Harry Smith.

On that fateful day, a small Australian company of 108 men - 105 Australians and 3 New Zealanders - found themselves vastly outnumbered by a determined North Vietnamese force estimated to be over 2000 strong. The Australians were based at a rubber plantation in Long Tan, surrounded by thick vegetation that hindered visibility and movement. The North Vietnamese launched an intense assault, employing small arms, mortars, and artillery fire.

Rain played a significant role in the Battle of Long Tan. The battle took place during the monsoon season in Vietnam, which meant that the weather was characterised by heavy rainfall and muddy terrain. The combination of dense jungle, muddy conditions, and torrential rain made the battle even more challenging for both sides.

The rain not only affected visibility and mobility but also impacted the effectiveness of weapons and equipment. The soldiers had to contend with wet uniforms, soaked ammunition, and the difficulty of maneuvering through the slippery and waterlogged terrain.

The trigger for the conflict was the Viet Cong's assault on the Australian operational base, Nui Dat, located at the heart of Phuoc Tuy. This attack occurred in the early hours of August 17, 1966..

Recently establishing the Nui Dat base, the Australians aimed to exert their influence over Phuoc Tuy, the province under Australian operational jurisdiction. Though the attack caused minimal harm, Brigadier Oliver Jackson, the Australian Task Force Commander, recognised the base's susceptibility to a significant Viet Cong assault.

In response, B Company of the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), was tasked with patrolling from the base to locate the Viet Cong's firing positions. Successfully accomplishing this mission, B Company was relieved by D Company, 6RAR, on the afternoon of August 18. D Company proceeded along tracks that led from the firing sites into a rubber plantation near the deserted village of Long Tan.

This would become the battleground, roughly 4 kilometres to the east of Nui Dat. As D Company advanced through the rubber plantation (with two platoons at the front and one behind), Lieutenant Gordon Sharp, commanding 11 Platoon on the Australian right, encountered a small Viet Cong contingent. Following a brief exchange, the enemy retreated eastward with 11 Platoon in pursuit.

At around 3.40 pm rifle platoons had their first fleeting contacts with scattered groups of enemy. The enemy uniforms, equipment and weapons, including AK47 assault rifles, should have warned the Australians they were enemy main force soldiers, not local guerrillas, but at first “the penny didn’t drop”.

The Australian troops were set to meet a huge number of enemy forces. Just past 4:00 pm, during the pursuit, 11 Platoon was under intense enemy fire. Lieutenant Geoff Kendall, leading 10 Platoon received orders to assist 11 Platoon. However, his platoon also confronted heavy fire that made it difficult to provide aid. Positioned behind D Company's leading platoons, Major Harry Smith, the company commander, alongside 12 Platoon and Company Headquarters, dispatched requests to Nui Dat for support as the company faced a grim situation.

Complicating the dire situation further was the disruption of communication, as gunfire had damaged the radios for both 10 and 11 platoons.

Unable to establish contact between 10 Platoon and 11 Platoon, orders were given for Lieutenant Kendall to withdraw his platoon and rejoin Company Headquarters. Meanwhile, Lieutenant David Sabben was instructed to move two sections from his 12 Platoon in a southerly direction hoping to reach 11 Platoon from an alternative path. However, Sabben's unit encountered resistance along the way and couldn't reach their intended destination.

As a result, D Company found itself fragmented into distinct groups, each subjected to relentless VC assaults. Among these groups, 11 Platoon faced the worst of it. Isolated from the rest of the company for an hour and a half since initial contact, more than half of the platoon's 28 soldiers had sustained injuries within just 20 minutes of the initial encounter.

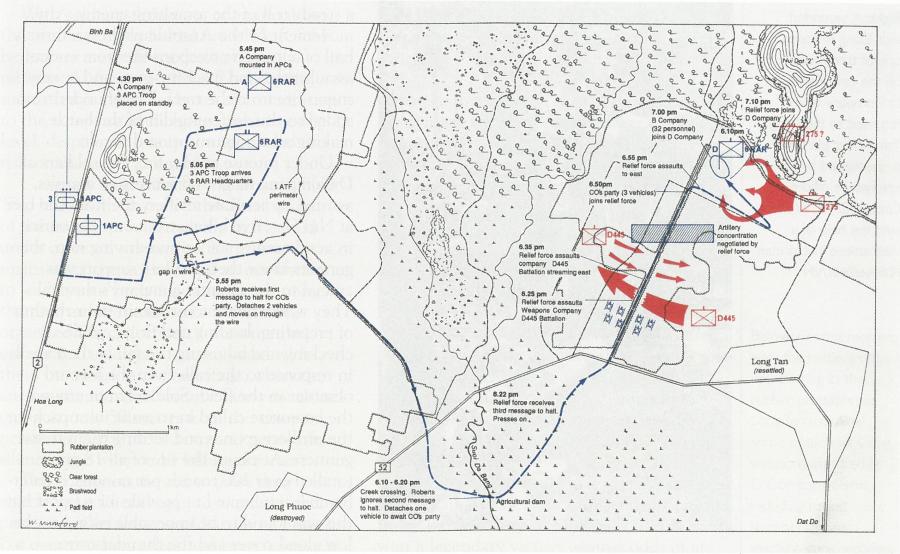

Progress of the relief force from Nui Dat to the besieged D Company in the Long Tan rubber plantation. (Reproduced from To Long Tan, by Ian McNeill, Map 15.1 - cartographer Winifred Mumford)

Back at Nui Dat, the Australian base was receiving reports from Long Tan. The figures coming in revealing the number of VC forces opposing the Australians were not encouraging. Allied artillery had already commenced firing on the VC positions, with Forward Observers embedded within D Company designating targets. The request for US air support was met, and three F4 Phantom jets were dispatched. However, due to thick cloud cover, they struggled to identify ground targets and ended up dropping their ordnance beyond the enemy's range. In a more successful endeavor, two RAAF pilots from 9 Squadron managed to navigate through severe weather conditions and delivered ammunition crates from treetop height to D Company, whose supplies were alarmingly low.

Later in the afternoon, a relief force was organised to assist D Company. First, B Company, which was returning to Nui Dat following an earlier mission, received orders to reverse course and locate D Company. Second, clearance was granted for the Armoured Personnel Carriers (APC) of 3 APC Troop to proceed and offer support to D Company. As a result, ten APCs departed Nui Dat with A Company, 6RAR on board.

Shortly before 6:00 pm, the surviving 13 members of 11 Platoon managed to retreat from their position and find their way to 12 Platoon, guided by a smoke grenade. Roughly half an hour later, capitalising on a temporary lull in the conflict, the combined forces of 11 and 12 Platoon successfully reconnected with the rest of the company. This marked the first time in the battle that D Company's strength was consolidated.

During the ensuing half hour, D Company endured relentless wave attacks. Fortunately for the Australian soldiers, the terrain they occupied sloped downward at their rear, offering a degree of shelter from the rifle and machine gun fire, most of which harmlessly sailed above their heads.

As night fell over the rubber plantation at 7:00 pm, the much-awaited relief for D Company materialised. B Company and the Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs) arrived simultaneously, their .50 caliber heavy machine guns unleashing a barrage through the rubber trees, disrupting the advancing formations of VC and causing them to scatter into the obscurity of night.

With the battle's end, although some members of D Company were eager to immediately return to the location of 11 Platoon, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend, the Commanding Officer of 6RAR who arrived with the APCs, made the decision to withdraw the Australians to the western perimeter of the rubber plantation. Here, the main focus was on evacuating the wounded. The true outcome of the battle gradually became clear in the subsequent days.

In essence, an Australian infantry company consisting of 108 men had successfully navigated an unforeseen engagement with two VC formations, later identified as the 275 VC Main Force Regiment and the D445 Battalion. These VC units had potentially fielded as many as 1,000 troops in contact with the Australians.

It is crucial to acknowledge that despite the VC's overwhelming numerical advantage, the Australians possessed their own considerable strengths – the fire support of three batteries from the 1 Field Regiment stationed at Nui Dat, supplemented by a battery of American medium artillery from the 2/35th Artillery Battalion. The personnel manning these artillery pieces worked tirelessly during the battle, firing nearly 3,500 rounds. Townsend estimated that at least 50 percent of the VC casualties were caused by artillery fire. However, due to the extensive shellfire, determining the exact cause of death for many of the bodies proved nearly impossible, as the battlefield had been ravaged. The arrival of B Company 6RAR and 3 APC Troop introduced an armored advantage that the VC lacked. Coupled with artillery support and aerial resupply, this mobility and firepower superiority offset some of the numerical disparity faced by D Company.

On 18 August 1966, in a rubber plantation near the village of Long Tan, Australian soldiers fought one of their fiercest battles of the war

— 🎀𝕂𝔼𝕃𝕃𝕀𝔼🎀 𝕀 𝕊𝔼𝔼 𝔻𝕌𝕄𝔹 ℙ𝔼𝕆ℙ𝕃𝔼 ™ (@kelliekelly23) August 17, 2023

108 men of 6th battalion faced 2000 enemy troops. Today we remember all who served🌹#VietnamVeteransDay #auspol pic.twitter.com/Hy12yixNcc

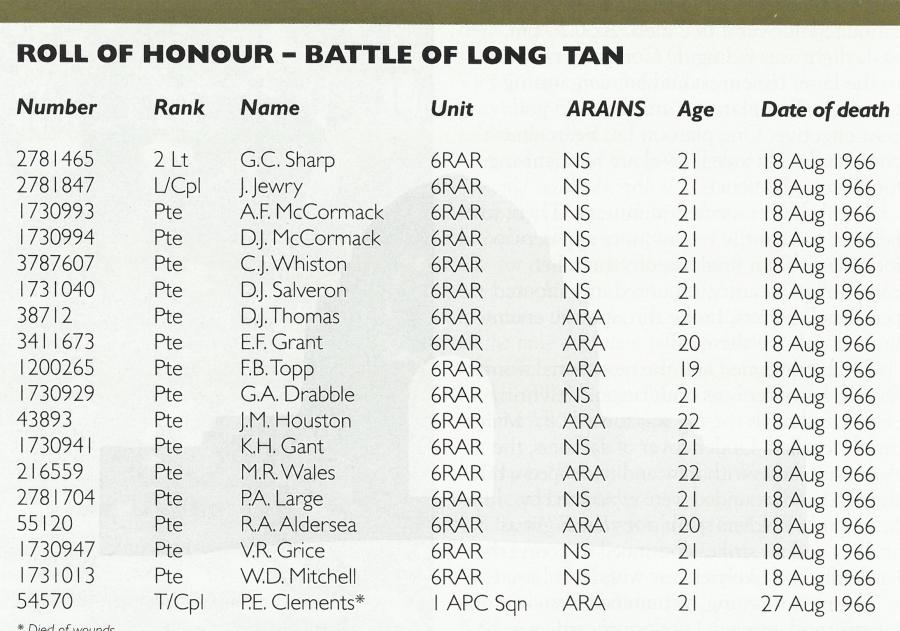

Australia’s actual casualties were 18 killed and 24 wounded.

Australian soldiers fought in scores of fierce actions during the war in Vietnam. Few were as intense or dramatic as the action in the Long Tan rubber plantation on 18 August 1966. An isolated infantry company of 108 men, cut off and outnumbered by at least ten to one, withstood massed Viet Cong attacks for three hours. They suffered the heaviest Australian casualties in a single engagement in Vietnam, but prevailed against the odds. Their valiant stand became a defining action of the war.

The legacy of the Battle of Long Tan serves as a reminder of the sacrifices made by soldiers in defense of their nations and ideals. The story continues to be shared as a source of inspiration and admiration for generations to come. Commemorative events, memorials, and discussions about the battle are integral in preserving the memory of those who fought and honouring their legacy.