They say Australia rode in on the sheep’s back.

But if you’d been standing in the cane fields of north Queensland, sweat in your eyes and the hum of harvesters in your ears, you might’ve thought otherwise. While the outback echoed with the bleat of wool and the click of shears, another Australia was rising... sweet, smoky, and sharp-edged. This one rode not on the back of a sheep, but on the swing of a machete.

The machete: tool of the land - now the weapon of headlines and a handy distraction from what’s really going on.

Our country, which owes so much to the machete, is about to ban them. So it got me thinking about sugar... its history and its contribution, good and bad, to our great nation of Australia.

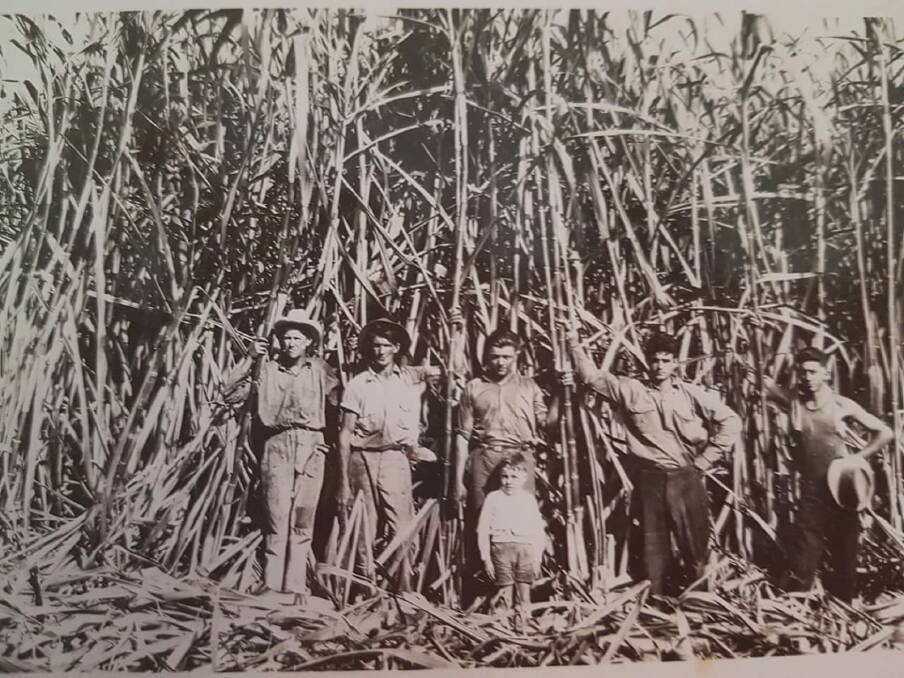

I once stayed with a friend who lives in the cane fields of northern Queensland. Her home is an old pub, weatherboard and proud, with fading photographs of Kanaka labourers on the walls - faces of sweat and guts, captured mid-harvest. The early Italian migrants who toiled and swung their machetes to earn a living in their new home.

My friend's husband, a cane harvester driver and a descendant of early Italian migrants, took me on a journey I didn’t expect: not just through the fields, but into the heart of an Australian history too easily forgotten.

I watched as his machine carved a path through the cane, which stood like green soldiers in the heat. Once, that harvest was done by hand - machete swinging under the sun, rhythm and danger in every stroke. We followed the harvest to the local Sugar Mill, where cane trains rolled in and lorikeets swooped down on the raw sugar - splashes of red and green against the pale golden pile. Later, at Lucinda Jetty, we stood watching the ships waiting to carry the sugar out into the world, just as generations before had laboured to send sweetness to distant teacups.

That night, over a drink in the pub, we talked of the Kanaka labourers - some tricked, many forced - and the Italian families who followed. There was pride and memory in the room. So much sweat. So much sacrifice. All to bring sweetness to strangers. Yet this vast history is rarely mentioned in school books, rarely celebrated in the way it deserves. While the west and south rode on the sheep's back, the north bent its back in the cane fields.

Experience the rhythm of the canefields through GANGgajang's classic track: Sounds of Then (This Is Australia).

When I first moved to Queensland, I remember visiting Nambour in winter and watching the sugar trains roll down the centre of town, heading to the mill. The smell of the cane filled the air. At night, the fields burned in orange lines against the dark, and I wondered why they did it - why the cane had to burn. We’d drive home from late-night shopping and see snakes scuttling across the bitumen, flushed from the heat and smoke. The cane trains stopped a long time ago. Down here in southern Queensland, cane fields gave way to housing estates and solar farms. Good solid agricultural land traded away for a myth of net zero, climate change policy, and corporate pockets eager for government subsidies.

The burning of cane, I later learned, served a practical purpose. It stripped away the dry leaves, known as trash, so that only the valuable stalks remained for harvest. It also flushed out or killed snakes and pests, making the work safer for labourers. In the days of manual machete harvesting, this was essential. Today, many places have shifted to green cane harvesting, leaving the trash as mulch to nourish the soil. But the old fires still flicker in memory, casting light on a time when flame, blade, and human hands worked in brutal harmony.

And now, the machete that once brought in the harvest is being banned in cities like Melbourne - not because it cuts cane, but because it has taken human lives. A spate of machete murders has led to swift political response. But in rushing to blame the blade, we risk losing sight of its original place in our story.

The machete was once an emblem of labour, of endurance. Of work done under the weight of the sun. Now it’s treated only as an object of violence. But maybe the problem was never the machete. Cain killed Abel with a stone, and David slew Goliath with one too. It is not the weapon. It is the hand that wields it.

This isn’t just about sugar. It’s about what we choose to remember - and what we allow to be forgotten. If we erase the past because the symbols make us uneasy in the present, we lose more than tools. We lose the stories. We lose the people. And we lose the hard-earned pride of places like the cane fields of northern Queensland.

Let this be the beginning of remembering. Let this be the start of a story worth telling in full.

We’ll be bringing you a series of articles about the cane industry - I hope you’ll enjoy them. Even Ratty News will stick a whisker in as a stowaway on an early blackbirding vessel, telling you his tales as a rat in servitude in the wilds of the north Queensland cane fields. He might even interview a cane toad. Who knows where this may lead?

But be warned: it’s a series you won’t want to miss.

Footnote: