In the closing stages of WW2 the Australian Army was given a role that offended the higher echelons of the defense forces.

While MacArthur and Nimitz were doing their island hopping towards the Japan, the Australian forces were given the task of mopping up areas already by-passed. This angered the likes of Blamey who saw it as a deliberate snub to Australia by not including them in the inevitable defeat of Japan.

I reject that notion completely.

The facts are that the Australian Army and Navy did not have the equipment needed to undertake amphibious operations. We relied entirely on the US Navy to provide the ships and landing craft vital to carrying out these operations. The US Navy had advanced so fast with its island-hopping strategy that all of its resources were needed for their own campaigns. I consider the protestations from our senior ranks to be nothing more than pompous pique and a dent in their inflated egos.

Secondly, the advances of the US forces was so rapid that there were vast areas where large Japanese forces were still in occupation and they had to be dealt with and liberated. This was Australia’s role and one for which our Army was very well suited.

Once New Guinea was free of Japanese forces the major area standing between it and the Philippines was Borneo.

Borneo was a vital link in the chain of Japanese occupied territory because it was its primary source of oil and a significant source of rubber. The oilfields of the British Protectorate of Brunei which stood between the states of Sabah and Sarawak together comprised what was then known as British North Borneo. The rest of the island was part of the Dutch East Indies. The Brunei oilfields were, and still are the oldest continuing working oilfield in the world.

The Allies developed a plan to invade and capture Borneo and Australia had the lead role in this campaign. The invasion of the entire island was to be undertaken in a series of different parts, predominantly Australian. The force to attack the oilfields was comprised of 22,700 troops, 6,000 RAAF and 1,000 US and British naval personnel under the command of Lt. General Leslie Morshead.

Operation AGAS was planned for 5 groups of specialist members of Z Force to move into North Borneo locations in Sabah and the Dutch part to the East to carry out reconnaissance and organise guerrilla units among the local people.

The first group of seven came ashore from the submarine USS Tuna in inflatable boats and kayaks, disembarking from the submarine 10 miles out to sea and paddling into shore early in March, 1945. Acting on intelligence reports, they reconnoitred the Sandakan camp of the Japanese and found it to be abandoned. They reported this back to Australia but they got it wrong. The camp had not been abandoned and, in fact, there were some 800 Australian and British prisoners still being held. Had their reconnaissance been correct they may well have thwarted the Japanese plan to embark on what became known as the Sandakan Death March.

One later group which was launched in this manner were never heard of again after they left their submarine. It is thought that the kayaks, being very low in the water and flimsy, were attacked by crocodiles and the men eaten. No trace was ever found. 10 miles is a long way out to sea in a kayak in the dark and these operations were by nature, undertaken on moonless nights.

At that time, the Allies were unaware of the Japanese plans for this tragic series of events which resulted in 2,434 Allied prisoners being forced marched in three groups to the village of Ranau, 260 miles inland. The marches took place in March, May and June of 1945 and of the original number only 6 survived.

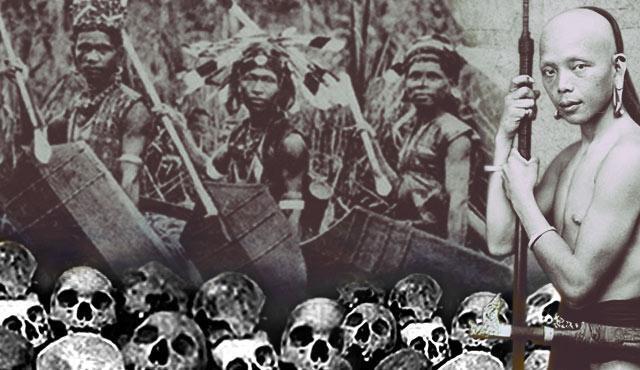

As a prelude to the invasion a small force of Australian commandos from Z Special Unit, were to be parachuted into Sarawak to recruit the local Dayak people to take up arms against the Japanese. The Dayak tribes inhabit the northern parts of Borneo. They were receptive of the Japanese when they were first invaded in 1942 recognising the superior Japanese strength but the brutality of life under the heel of Nippon soon turned them off. Conversely, there was no certainty that they would be willing participants on the Allied side. The Dayaks were traditional head-hunters. A practice that the former colonial administrations had tried to stamp out with limited success but it was part of the way of life for these people.

In March, 1945 the small force of 8 of these specialist Z Force commandos jumped from a Liberator bomber into the village of Bario, in Sarawak, not knowing what kind of a reception they would get or whether there were Japanese occupying the area. It really was a suicide mission. Their role was to recruit and train the Dayaks into a guerrilla force. This group was part of a separate operation called SEMUT and was specifically directed at the capture of the Brunei oilfields. They were the first of three groups making up Operation SEMUT.

On landing they were welcomed with open arms by a people of which there was very little knowledge and many of whom had never seen a white man. However, lengthy negotiations were needed to convince the local people to form themselves into groups lead by the Australians who were seen as being part of the former colonial regime. Despite this apparent handicap the commandos were successful in recruiting the needed numbers. In the end about 600 Dayaks were recruited and formed into guerrilla groups. In other theatres where local forces were recruited the system was that the locals would join the Australian units. The reverse was the case here as there were no Australian units as such, just 8 individual commandos who then joined the Dayaks units.

They lived with the Dayaks in their villages, went on patrols with them and learned the skills of ambushing, Dayak style. The traditional weapons of the Dayaks were the parang, a razor sharp machete used for cutting off heads, and blowpipes from which they ejected poison tipped arrows with great accuracy. The long houses in which the commandos lived were decorated with skulls accumulated over the years from unfortunate enemies and the villages were generally adorned with them as well.

The commandos learned to use the blowpipes. They had little option because they were not supplied with an array of guns and ammunition. They patrolled the jungle and set up ambushes as if they were a part of the tribe. This first group accounted for about 1,000 Japanese killed with no losses of their own but 30 Dayaks lost their lives. This group and the two that followed comprised 82 Australian soldiers with no losses, about 1,500 Japanese killed and 240 taken prisoner.

As an incentive to the Dayak recruits, the Australians paid 5 Dutch guilders for every Japanese head brought in. It was a lucrative pastime for the Dayaks and it terrified the Japanese. At this stage of the war the Japanese had been all but abandoned by Tokyo. There was a critical shortage of supplies and no reinforcements of fresh troops. The terror inflicted by the Dayak tribesmen required that no Japanese soldier ventured beyond their camp alone. As they moved in groups they were prime targets for ambush. The tribesmen engaged in this work with great enthusiasm the cash rewards being simply a bonus.

Headhunting by the Dayaks was not confined to the SEMUT group. In March 1945 11 teams were placed into Sarawak by submarine, parachute and flying boat. One canoe, folboating in from a submarine was lost, never to be found. Another was shadowed by a large crocodile the length of the canoe and made visible by the phosphorescent glow of the moving water.

Most of them made it and were soon welcomed by the Dayaks because they condoned headhunting. The large number of these Platypus groups attracted Japanese activity and there were a number of skirmishes. In one of these the commando leader bayoneted a Japanese soldier. On returning to the Dayak village the head man presented the soldier with a bag. Inside was the head of the Japanese he had killed and it was his, by right, according to Dayak tradition. As his personal trophy of war.

The Dayaks then proceeded to instruct him in the science of preserving the head. First, a tuft of hair was removed and carried in the victor’s belt. Next, the head was strung by the remaining hair over a gentle smoking fire so that he heat rose then gently cook the head and shrink the skin. AS the skin shrank it eventually split and fell off the head together with the remaining flesh leaving the grinning skull. The skull then became the personal property of the victor and was mounted on his bedpost in the long house where he slept. All heads acquired were treated in this way and there was a steady accumulation.

After the war ended, actions were still being undertaken against recalcitrant Japanese but on September 12th orders were given that further actions were forbidden. Orders were passed to the Dayaks that no more Japanese were to be killed. Two days later the commandos were presented with a bag full of heads. Chinese. The head man was disciplined and his response was that he had followed orders. They were ordered not to kill any more Japanese but these were Chinese, traditional enemies of the Dayak. The Commanding officer had no option but to concede that the head man was correct.

The surviving Z Force members were all evacuated by submarine and flying boat leaving their trophies behind them.

The early work undertaken by the various Z Force groups resulted in the successful retaking of Borneo by the Australian Army with landings at Labuan, Tarakan and Balikpapan.

Unfortunately they were unaware of the Sandakan Death march until it was too late.

The exploits of the Z Force groups were kept unknown to the Australian public. Z Force was part of the command of Special Operations Australia (SOA). Its members were sworn in under the Official Secrets Act and no disclosure of their activities was permitted for 35 years after the war ended. That included disclosure to family members. About 75,000 Australian soldiers took part in the Borneo campaign but the activities of the 100 or so Z Force members who preceded them was a closely kept secret.

Subsequently, the disclosure of our troop’s activities in reviving, encouraging, aiding and abetting in the practice of head hunting drew much tut-tutting from the chardonnay set and their ilk. The same mob who criticise the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. What these people do not realise is that there was a war on and the effect on Japanese morale was significant. They had been brought up on a diet of atrocity with impunity in 1942 and 1943. Now they were getting some of their own medicine and they did not like it at all.

The average soldier goes into battle with his eyes wide open in the knowledge that he may be wiped out by gunfire, mortar and artillery fire, possibly by bayonet or knife but the thought of being beheaded by one stroke of a razor sharp parang is terrifying. The Ghurkhas enjoy the same magical advantage with the terror infused kukri for which they are famous yet nobody has objected to that, have they?

The downside of the secrecy provisions was that none of the participants were able to receive awards for their bravery and contribution to the war effort. Officially it never happened.

But we must never forget.

Operation SEMUT is cited as being the most successful stealth operation of the Second World War.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS